Gail Hastings professes to be a sculptor, but she is an unusual one. Her works often consist of such unfamiliar sculptural media as watercolours or pencil drawings. Her subject matter is equally unusual. It often features pages that look as if they have been transplanted from some esoteric encyclopaedia or otherwise may contain snippets of an overheard conversation. These tantalising elements are in turn ‘housed’ within Hastings’s finely constructed abstract, geometric spaces.

The effect is like walking into an abstract painting, except to say that one may also encounter text, specially devised furniture or intricate floor plans that actively shape the space of the work. Hastings regards her works as ‘sculptural situations’ rather than as paintings or installations, or even sculptures. Rather than adhering to a pre-existing location, Hastings seeks to craft space – in particular, she seeks to craft an inter-subjective space, a social space of conversation and communication. This is at once a remarkably fraught, ambitious and fascinating enterprise. It is also one reason why the experience of Hastings’s evocative situations is like confronting something vaguely familiar, yet weirdly opaque.

Hastings thinks of our inter-subjective space as a kind of invisible architecture comprised of both intersecting and dissecting personal and public-social trajectories. Think of how conversations in cafes are usually private, sometimes intimate, although they are conducted in a highly public forum and thus often easily overheard. Or think of how mobile phone conversations connect two people in quite separate places, while at one end a participant may carry on the conversation quite audibly and unselfconsciously as if ensconced in some imaginary private booth. Once the speakers hang up, it is as though they have been transported back to the formal composure of public space.

We are constantly reminded that we are social beings, but our shared space is often the arena of our greatest anxieties as much as of our greatest joys and satisfactions. The ideal of public space and of conversation is the perfect accord: every voice heard and the coming together of contrasting elements in the golden glow of harmonization. Our anxieties intrude when we feel that this ideal evades us or when we are left to negotiate less than satisfactory social transactions. The ideals of art were once very similar – the perfect accord, the ideal narrative – yet today contemporary art addresses different ambitions by focusing upon the peculiar in the familiar and giving the readily familiar a peculiar outlook.

Hastings is very contemporary in this sense. She professes her frustration at the struggle ‘to make actual space perceivable in a work of contemporary art’ even though it is the great ambition of her work. This is perhaps why the superbly crafted spaces of Hastings’s work convey an air of serenity or of determined order, while at the same time leave the lasting impression of some kind of riddle or mystery. The visual-textual cues invariably deposited around her elegant, abstract spaces hint at some undisclosed plot. These cues actually constitute a set of disparate spatial-temporal markers delineating the seemingly tangible, but elusive ‘architecture’ of inter-subjective space. The works thereby hinge upon an ambiguous aspiration: they strive to present the most composed and tightly unified work possible, while devising a space sufficiently evocative that it is open to vivid and at times unaccountable inter-subjective projections.

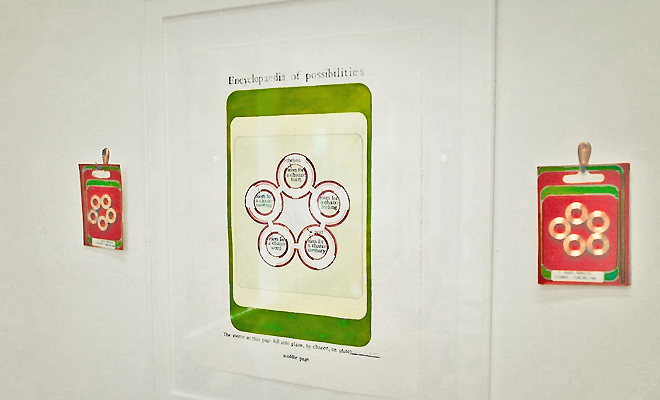

Hastings’s sculptural situations often interweave disparate clues suggesting a transit in time and space. The employment of spatial and temporal cues is one of the distinctive features of Hastings’s art. In an earlier work, Encyclopaedia of a moment’s evidence 1993, each fastidiously designed and hand-rendered page – purportedly from this cryptic encyclopaedia – looks like some arcane activity sheet recording a mysterious quest for knowledge. The passage of time is surreptitiously inscribed in Times font, yet the page numbers do not reveal a sequence at all but simply repeat page five each time. They appear like pages from an unfathomably stalled text because the sequence goes nowhere, except spatially from room to room. We encounter a busy, episodic circuit signalling a pursuit or a quest, as if striving to render significance, although barely registering in time.

Plate 3: Moment 12.00pm

At 12.01, she hurriedly enters room A

in urgent search for the evidence of mo-

ment 12.00pm. She finds it. [5]

Plate 4: Moment 12.00pm

At 12.01, assured that the evidence of

moment 12.00pm was in room B, she

entered, but too late. The evidence had

been wiped away. [5]

Plate 5: Moment 12.00pm

If evidence of the moment 12.00pm ex-

isted, it would be found in room C. She

enters room C at 12.01 and she finds no evi-

dence of moment 12.00pm. [5]

The clipped syntax mimics the text inscribed by an old typewriter, which harshly ‘justifies’ the lines by abruptly breaking words in two (even though every line of the work is carefully delineated by hand). Breaks too occur in the flow of ‘evidence’. Is a case building, or evaporating?

A different example of such temporal-spatial puzzles is found in Room for love 1990, which contains a conversational or ‘tête-à-tête’ chair, an S-shaped two-seater sofa, sometimes called a ‘love chair’. In such a chair, two people sit in close proximity facing in opposite directions, although they can also converse face-to-face. For Hastings, the analogy alludes to the often-fraught dynamics of social interaction as well as to the reception of art: ‘the chair was intended as a conversation with oneself when one looks at a work of art – where two opposing views are struck – literally –while there is also this third, reconciliatory view of turning halfway toward the opposite view’.1 [See a detail image of Room for love above]

The analogy is highly suggestive. For instance, this piece of writing aims to explicate the work for a reader who may have already experienced it, but like the ‘tête-à-tête’ chair it aims to turn the viewer around again to face the work, although differently. It may even extend the understanding of the work beyond conceptions ordinarily entertained by the artist. The analogy also recalls the puzzled status of art in the wake of post-minimalist art, which prompts questions such as: what is the ordinary, quotidian object and what is the artwork? What does it do? As the art historian Thierry de Duve notes of the minimalists, ‘far from freeing themselves “from the increasing ascetic geometry of pure painting”, the minimalists claimed it and projected it into real space’.2 This is what Hastings does, except that she stage-manages this extended state of puzzlement over the status of art.

With her latest work, referencing Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahoney Griffin’s partially realised plan for Canberra, Hastings shifts attention from puzzlement over the confounding qualities of post-minimalist art to the earlier aspirations of such abstract, geometric visual languages associated with the urge to forge a common, equitable social space. This ideal was typified by the Griffins’ thwarted plan to place a library at the apex of Capitol Hill just above Parliament House. Hence, the aim was to erect a space for knowledge and reflection at the apex of its social-symbolic space, a place devoted not only to historical memory but to the on-going articulation and re-articulation of the shared space of a nation. The Griffins are perfect for Hastings’s purposes because they intertwine the aspirations of an abstract visual language with a similar concern for social space – and this has tempted some to interpret secret or esoteric meanings behind their elaborate designs.3

Hastings perhaps recalls an ideal space for art, but one that has escaped it throughout modernity. Her persistent and distinct art practice attempts to yield an inter-subjective space, which defies her as well as art in general, but which also eludes each and every one of us daily. Yet such an irrevocably intangible space is regularly experienced in keenly felt ways and this is what Hastings magically aims to manifest. The Griffins once aimed to make the ‘invisible architecture’ of a nation explicit whereas today (ironically) it lies buried within the confines of parliament. In striving to make that invisible architecture of intersubjective space perceivable, Hastings’s art rearticulates that vision for a contemporary audience. Hers is an art, however, that evokes the formal composure of the original Griffin plan – with its ideal apex now buried and remote – and we soon realise that it is attuned to what may just as readily escape us in conjuring this formal composure.

- Gail Hastings, private communication with author. [↩]

- Thierry de Duve, Kant after Duchamp, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA 1996, p 218. [↩]

- James Weirick, ‘Spirituality and symbolism in the work of the Griffins’ in Anne Watson (ed), Beyond architecture: Marion Mahony and Walter Burley Griffin in America, Australia and India, Powerhouse Publishing, Sydney 1998, pp 56–85. [↩]