When someone a couple of years back asked what sort of art I make, I hesitated. Easy to answer if one makes either painting or sculpture; difficult, if one makes neither. Worse, still, if one makes a spatial art that is not ‘installation’. For which reason I asked, in response, ‘Do you know of installation’? ‘Yes’, she replied. ‘Well—I don’t make that’.

Before I could continue, I was asked if I am Irish. Thinking she had politely changed the subject, I tried as best I could to describe my ancestry. ‘Figures’, she said. ‘It is a bit like asking Paddy:

“Hey Paddy, can you tell me where the nearest pub might be?”

“Ai, my friend, do you know where McCleery Street is?”

“Yes Paddy.”

“Do you know where it intersects McAuley Street?”

“Yes indeed, Paddy.”

“Well, it isn’t there”.’

Point taken. In other words, why point to a positive attribute—a ‘this thing here’—only to say one’s art is not that. Having done so reveals the extent I am desensitised to the non-sense that defines the art I practice; a glitch or necessary blind spot, nevertheless, under which to labour. For invariably, to discuss the art, one has to drive to ‘neither-nor’ places to enable a glimpse of that which contemporary commentary is bereft.

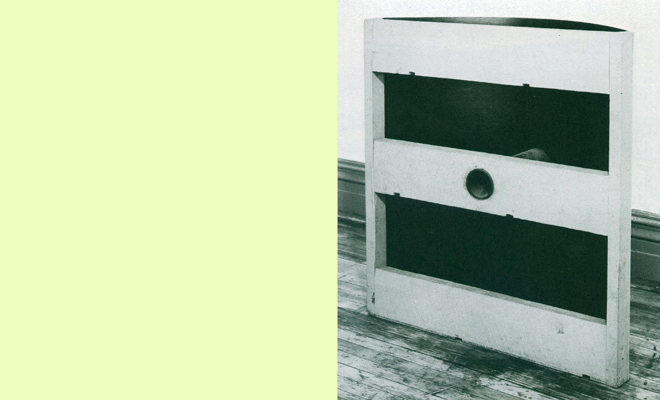

When, in a survey article published in 1965, the artist Donald Judd wrote ‘Half or more of the best new work in the last few years has been neither painting nor sculpture’, ((Donald Judd, ‘Specific Objects’ (1965) in Complete Writings 1959-1975: Gallery Reviews, Book Reviews, Articles, Letters to the Editor, Reports, Statements, Complaints, Halifax, Nova Scotia New York Press of Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, New York University Press 1975, p. 181.)) little could he image that forty-five years later we would still be stuttering his ‘neither-nor’ description, with no advance on a positive identification. Aiding and abetting such stagnancy, it would seem, is a conflation of ‘neither-nor’ with the Proun Space (an ‘interchange station between painting and architecture’) of Russian artist El Lissitzky (1890-1941), to result in an understanding that turns neither-nor into a nowhere land ‘between painting and sculpture’; an understanding that in fact excludes the space upon which both Donald Judd and, one might argue, El Lissitzky focussed.

What is Proun Space? The word ‘Proun’ is an acronym of a Russian phrase comprising three words. The first three letters and the first letter of the remaining two words spell ‘Proun’. ((El Lissitzky, ‘Life, Letters, Text’, ed. Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers, Thames and Hudson, London, 1967, p. 401, fn. 7.)) The phrase, when translated, means ‘Project for affirmation of the new’. Yet, after Herbert Read mentions this in his introduction to El Lissitzky’s letters, he tells us,

‘But there was never anything essentially new in Lissitzky’s style: it was a synthesis of elements taken directly from the ‘suprematism’ and from the ‘constructivism’ of Malevich, Tatlin and other Russian artists’. ((ibid., p. 7. Note, Herbert Read translates Proun as ‘project for the establishment of a new art’.))

Many commentators, since, abide Herbert Read’s discernment and overlook El Lissitzky to go directly to the named sources of the ‘new’ (Malevich, et al.). In so doing, they overlook a type of space that remains without a phoneme of its own in our contemporary art lexicon and thereby remains ‘new’, today.

Not so, however, with Sophie Küppers who, at the time, recognised something very different in the Proun compositions El Lissitzky had been making since 1919. Fascinated upon seeing them the first time at the Exhibition of Russian Art in Berlin in 1922, Sophie obtained El Lissitzky’s address from the Exhibition’s office in hope of exhibiting this ‘new art’ at the gallery she ran, the Kestner-Gesellschaft, in Hanover. ((ibid., p. 11.)) The two met later that year in Hanover, the exhibition took place in 1923 and the two married in January 1925. ((Eric Dluhosch, ‘Translator’s Intorduction’, in ‘El Lissitzky: Russia – An Architecture for World Revolution’, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1989, p. 15.)) For Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers, El Lissitzky’s Proun compositions were ‘a cosmic space, in which floating geometric forms were held counterpoised by tremendous tensile forces. They were three-dimensional, in contrast to the suprematist compositions of [K]asimir Malevich which gave an effect of absolute flatness and fragmentation’. ((El Lissitzky, ‘Life, Letters, Text’, ed. Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers, Thames and Hudson, London, 1967, p. 11.))

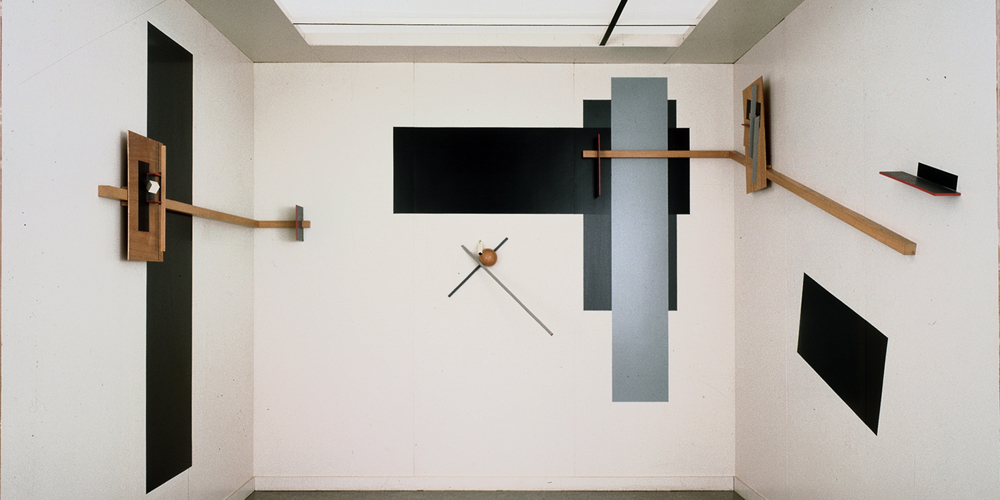

It is largely this difference, recognised by Küppers, that came to the fore in El Lissitzky’s Prounenraum made for the Great Berlin Art Exhibition of 1923, at the Lehrter Bahnhof (1871) where, today, the Berlin Hauptbahnhof (2006) stands. Given a boxlike space at his disposal, El Lissitzky utilised the intended ‘six surfaces’ (four walls, ceiling and floor), except the floor. ((El Lissitzky, ‘Russia – An Architecture for World Revolution’, tr. Eric Dluhosch, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1989, p. 139)) Black, white and grey geometric elements stacked either flat on the wall, in relief as wooden assemblages, or protruding as perpendicular wooden slats (‘with a flash of red’), organise the space ‘in such a way as to impel everyone automatically to perambulate in it’. ((ibid.))

Where, in the earlier Proun compositions, clusters of geometric forms generated a vanishing point contradicting that of the cluster immediately alongside due to separate axes; in the Prounenraum of 1923, the perambulating person moving through it enacts this multi-perspectival viewpoint within a similarly singular space. From right to left,

‘the surface of the Proun ceases to be a picture and turns into a structure round which we must circle, looking at it from all sides, peering down from above, investigating from below. … Circling around it, we screw ourselves into the space’. ((El Lissitzky, ‘Life, Letters, Text’, ed. Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers, Thames and Hudson, London, 1967, p. 347. It occurs to me that El Lissitzky, quite possibly, had one follow the room from right to left in the manner Hebrew is read, much in the same way gallery spaces in English speaking countries often organise their space from left to right.))

Opposing perspectives seen from above and from below install a movement between extremes realised, here, to make space a ‘plastic form’. ((ibid., p. 347.)) In this way, a Proun space might occur through: a cube (on the left Prounenraum wall) in opposition to a sphere (on the wall preceding it); ((El Lissitzky, ‘Russia – An Architecture for World Revolution’, tr. Eric Dluhosch, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1989, p. 139)) no perspective in opposition to perspective; two-dimensionality in opposition to three-dimensionality; or painting in opposition to architecture; all within one space—to create that space.

Central to an evaluation by Claire Bishop of El Lissitzky’s Prounenraum with respect to ‘Installation Art’, is its perambulatory nature said to anticipate ‘Merleau-Ponty’s account of embodied vision’. ((Claire Bishop, ‘Installation Art’, Routledge, New York, 2005, p. 80.)) Many regard Phenomenology of Perception (1945) by the philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908-61) as key to so-called Minimal art. ((Hal Foster, Rosalind Krauss, Yve-Alain Bois, and Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, ‘Art since 1900’, Thames and Hudson, New York, 2004, p. 494.)) Accordingly, it is perceived Merleau-Ponty, ‘against Descartes’ and any ‘form of idealism’, grounded our being in ‘the partial nature of visual experience due to the “perspectival” limits of human perception’. ((ibid., p. 495.)) The ‘relativism’ of this mono-perspectival ‘embodiment’ is now a general riff that plays through contemporary art history. ((While some may not only disagree with this summation of Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s philosophy but disagree, as well, with whether his philosophy influenced Minimal art, I have taken this understanding from ‘Art since 1900’ given its increasingly prominent use as a resource for a general understanding in contemporary art history.))

Nevertheless, the evaluation by Claire Bishop appears at odds with the fact El Lissitzky’s Proun Space in not mono-perspectival, but multi-perspectival. It is in the act of going beyond the limits of human perception as a singular-point perspective that constructs a multi-perspectival Proun space. In defiance of relativism, it is our conceptual movement beyond ourselves that enables an embodiment in which we ‘screw ourselves in’. In 1966, Joost Baljeu asks, ‘What does a Proun express? Infinite space? Emptiness?’, by way of reply he quotes El Lissitzky:

‘The energetic task which art must accomplish is to transmute the emptiness into space, that is into something which our minds can grasp as an organised unity’. ((Joost Baljeu, ‘The new space in the painting of El Lissitzky’, in El Lissitzky, ‘Life, Letters, Text’, ed. Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers, Thames and Hudson, London, 1967, p. 390.))

While in 1924, in a magazine compiled with Hans Arp called ‘The Isms of Art’, El Lissitzky defines Proun as ‘the station for change from painting to architecture’, in 1925 he writes ‘I cannot define absolutely what “Proun” is’. Sophie Lissitzky, however, refers to a 1928 definition, ‘the interchange station between painting and architecture’, generally quoted since. ((El Lissitzky, ‘Life, Letters, Text’, ed. Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers, Thames and Hudson, London, 1967, p. 21. Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers appears to quote from a ‘personal confession’ entitled ‘Lissitzky Speaks’ (p. 330) and not, as some seem to think, from a statement written to her in a letter.)) Rather than treat this interchange station as a location neither here nor there, a destination not yet reached after a departure some time ago, Joost Baljeu instead interprets it as ‘the station at which art changed trains for architecture’, wherein art became a ‘construction of space’. ((Joost Baljeu, ‘The new space in the painting of El Lissitzky’, in El Lissitzky, ‘Life, Letters, Text’, ed. Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers, Thames and Hudson, London, 1967, p. 392.)) After all, this literally took place at the Lehrter Bahnhof: not a nowhere station ‘in-between’ but at the end of the Lehrte-Berlin line—a definitive location.

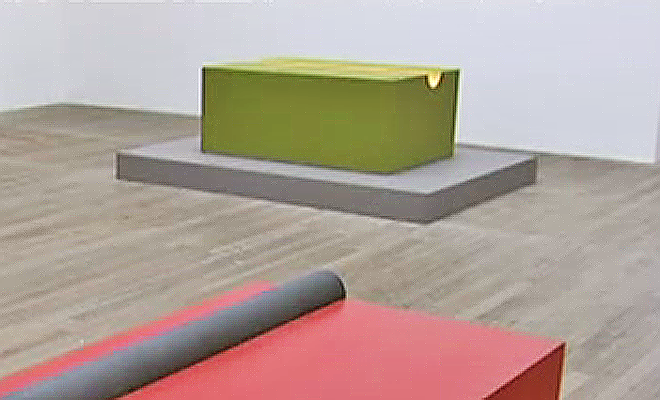

In emphasising this, it is not to say a spatial construction excludes either painting or sculpture. Rather, if we focus on ‘spatial construction’ instead of slotting this art ‘between painting and sculpture’, we might finally find the positive terms with which to describe spatial art, rather than let it remain within the silence of an ‘in-between’ land that is ‘neither-nor’.