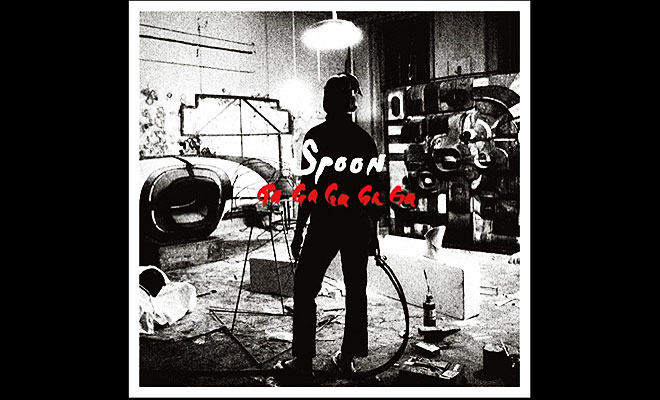

While browsing iTunes one fine July 2007 day, I happened upon a new release by Austin Indie band ‘Spoon’ with a cover image of the artist Lee Bontecou by photographer Ugo Mulas, taken in 1963.

Instantly impressed, I eagerly investigated further and came across an interview. Here, singer/guitarist Britt Daniel explains that, although he was not aware of the sculptor before coming across the image, the image immediately struck him as typifying the mood he felt about the record. ‘It’s just this guy, Bontecou, looking at all these pieces of debris’ says the interviewer, to which the singer replies, ‘Yeah, and they’re weird pieces. Or colorful. They just are’.

While I suggest the singer had his band’s songs more in view than Lee Bontecou’s art by his reply (as Lee Bontecou’s art, of that time, was pretty much dark and light with a lot of dirty looking tones between), what is nevertheless startling is that, rather than inform the interviewer Lee Bontecou is female, the singer instead revealed he, too, thought Lee Bontecou is male; for which reason, it now becomes obvious, he felt an affinity.

The mistake would have been mortifying for the singer once discovered, which it was, as made evident by another interview some weeks later. Had he realised earlier, the impetus behind the cover’s selection would not have been there and another image would have appeared in its place. So I am glad of the mistake, as it has produced one of the most arresting album covers I have seen in a long time.

Although these mistakes are everyday and unworthy of being held ransom to, this one is nevertheless uncanny since it bespeaks a silent tragedy that has throttled a vital understanding of contemporary art from around the time the photo was taken up until today. For what this mistake reveals—given the singer most likely comes from a progressive background—is that even under such an enlightened perspective, an innate prejudice still persists in society to the extent certain postures are read as male, only. The blowtorch, a back turned rather than a front offered, independence of mind, an absorption in one’s work, a disdain for conformity, taking one’s time and our gaze directed in a non-objectifying way spell male artist, not female. If this is now, no wonder Lee Bontecou’s art was treated as threatening in New York’s decidedly male dominated art scene of the late 1950s—back then.

For these reasons, Lee Bontecou’s art could have easily been dismissed by the minimalist artist Donald Judd who was on the job, at the time, as an art writer as a means to fund his then relatively unknown studio practice. If the catalogue essay for the present exhibition Less is More is right in its description—where, ‘for him, less (or non) of some things—symbol, narrative, illusion, incident—meant more of an emphasis on others—like dimensionality, shape, ‘material as material’ and an engagement with real space’—then Donald Judd’s dismissal of Lee Bontecou’s art should have been par for the course. But, it wasn’t.

Instead, Donald Judd recognised in Lee Bontecou’s art a paradigm shift. Even the term most associated with Donald Judd—‘specific objects’—was first formulated, as the art historian Richard Shiff points out, in 1963 when describing a Lee Bontecou relief as ‘actual and specific and … experienced as an object’. (GH, The process of specific space, 2009.)

According to the New York Times art critic Roberta Smith, Specific Objects is one of the three most significant contemporary art essays to this day (ref). The other two are Clement Greenberg’s Modernist Painting (1960-1) and Michael Fried’s Art and Objecthood (1967). It was written in 1964 when Donald Judd was assigned to write a survey article of the present art situation, yet was not published until the end of 1965. Its opening sentence is now iconic: ‘Half or more of the best new work is the last few years has been neither painting nor sculpture’. (ref.) Written afterwards, though published months before, is another text by Donald Judd that opens: ‘Lee Bontecou was one of the first to use a three-dimensional form that was neither painting nor sculpture’. (ref.)

In these works by Lee Bontecou of that time (see Slide 4 above), we see an eruptive force explode a gridded picture plane into the actual space of the room. ‘Bontecou’s constructions stand out from the wall like contoured volcanoes. Their craters are voids but exceedingly aggressive ones, thrust starkly at the onlooker; these are threateningly concrete holes to be among’, wrote Donald Judd in 1960. The resulting radiation of concentric circles intrude upon the usually segregated space of a viewer, with a black gaping hole at the centre.

‘The black hole does not allude to a black hole; it is one’, wrote Donald Judd in 1965. Posited, then, at the centre of a pictorial space was a black hole of real space. In being real, the usual segregation between the pictorial space of a work of art and the real space of a room in which we look at that work of art, had been violated. As a result, the artwork’s black hole moves between opposing poles as a space that includes us (real space) and a space that excludes us (pictorial space).

Upon observing this dialectical action of space, Donald Judd took it back to his studio as a tool that helped redefine his art into the art we recognise as his, today. He later describes it as created space. It is an active space opposite to the space we have come to know through the writing of Robert Morris, which is a passive space—such as the given space of a room. The difference between the two may be difficult to comprehend, especially as Donald Judd is broadly known as laying heavy emphasis on the ‘given’ — on ‘material fact’— which would lead one to think the space of his art is the same room space as Robert Morris’, but it is not. Real space, for Donald Judd is not found as is the space of a room, but created.

To understand this difference we have to remember Donald Judd majored in philosophy at Columbia University. Much in philosophy focuses on the question of truth, such as: how do we know the representation of an object in our thoughts corresponds with the actual object outside our thoughts. In other words: how do we know we are not just imagining it? Post-modernism’s reply is that we cannot know, since everything is relative: what I see from my perspective will be different to what you see from your perspective.

If we are locked into our own perspective, then it is easy to be held captive by our own prejudice. We see an example of this in America’s political far right, who insist President Obama has no legitimacy to be President since he was not born in America; a belief they hold onto even though the White House has released the President’s birth certificate (the fact of the matter) that proves otherwise. Relativity, therefore, knows no bounds; facts don’t figure.

You can see why Donald Judd would not have championed post-modernism and its accompanying relativism, given he was on the side of facts. What this means is that, rather than start from a position of self-certainty, barricaded in by one’s own perspective, one instead starts from a space of uncertainty, moves beyond it, takes up the space of the other (facts), from which one then returns with knowledge of the other. As Richard Shiff has said, ‘Judd was more of a viewer than most viewers are … [he] recognised the danger of starting his position as definitive’ (ref). Instead of a perspective without bounds, facts—the other—holds it in check. In philosophy it is known as intersubjectivity. It is the opposite of relativism.

When Donald Judd observed a dialectical act of space in Lee Bontecou’s art, he recognised in it the dialectical act of intersubjectivity. Thought, then, that creates this dialectical act of space does not take place in the private space of oneself, but the public space outside oneself: the space of the other, of ‘facts’ — the artwork.

As I have written earlier:

Robert Storr, when recently writing on Lee Bontecou who ‘dropped out of the art world at the height of her fame in the mid-1970s’, points out that, ‘Writing someone back into art history thus entails risks both for the writer and the artist’. Critically unmeasured advocacy, or ‘sins of commission’, can cause more damage than past writers’ ‘sins of omission’.

Without refrain, nevertheless, Robert Storr little flinches when pointing out one drastic omission in particular, that of Lee Bontecou’s work by Rosalind Krauss in Passages of Modern Sculpture (1977); a book that ‘established the canon for many curators and critics with power in or over major institutions’. Drastic, in that, to ‘be left out of the book meant oblivion in many academic circles where histories are constructed’.

Mentioned are just five women sculptors: Louise Bourgeois, Barbara Hepworth, Eva Hesse, Louise Nevelson and Beverley Pepper. ‘None except Hepworth and Pepper rate more than a line or two and a text figure’.

With this he points out, ‘Robert Morris, the sculptor-critic of the 1960s to whom Krauss’s work is heavily indebted, did not discuss Bontecou in his Continuous Project Altered Daily’; added to which, ‘Krauss’s other mentor Clement Greenberg did so once, only in passing and disparagingly at that’ (ref).

In a footnote Robert Storr adds:

I have emphasized Judd’s role in critical literature on Bontecou in part because his ability to recognize and eagerness to champion her work are key to understanding his position. Judd’s … tough-minded thinking … never takes the fatal step into prescriptive or proscriptive dogma commonly taken by other formalists of the period. Like Lippard, Judd was a writer of strict standards, and was open to arguments that diverged from the perspectives he primarily adopted. Although opinionated, he was an aesthetic empiricist and a pluralist. Moreover he was alert to artists work outside the mainstream, and seemingly at odds with the classicism of his own approach, as if these artists spoke for the eccentric or grotesque parts of his own sensibility that he had subordinated to his formally severe methods and means. (ref)

In accrediting Donald Judd for championing Lee Bontecou’s art, we also see Robert Storr flounder a bit in trying to understanding why he did so, to end up suggesting Lee Bontecou’s art may have spoken for a subordinated part of his own, when nothing of the sort is the case. Yet, to suggest this indicates Robert Storr is not familiar with the type of space of Donald Judd’s art, nor the role of Lee Bontecou’s art in its genesis. This is not surprising for the reasons he himself has revealed, in which we see the effect of an invisible misogyny determining an art historical account even in modern times.

This is also apparent in James Meyer’s books on minimalism in which the space of Donald Judd’s art always comes off as a poor man’s Robert Morris, since Robert Morris’ is the only understanding of space the writer acknowledges. Within its context Donald Judd’s art is judged both badly and mistakenly.

The Less is More catalogue follows this pattern and, by doing so, reenacts an inherited misogyny. As a result, Donald Judd’s main concern is left out: created space.

Minus its proper nomenclature (‘created space’) and minus recognition of its genesis, this is the space to which I was introduced as minimalism when an art student in the late eighties at the VCA, Melbourne. Sitting in the dark of a slide show, with an art history teacher decrying again and again ‘but don’t you see’ while projecting an image of a Donald Judd piece (see Slide 5 above), I have to admit at first I didn’t. No matter the times he described the work in terms not unlike those I’ve used to describe Donald Judd’s observations of Lee Bontecou’s art, and no matter how beseeching his ‘but don’t you sees’ became—I just didn’t. All I could see was a grainy black and white photo of a number of fabricated metal boxes lined up in a row, industrial looking, hard, uninviting, purposively made yet seemingly pointless—with another row mounted on the wall behind. None of this seemed ‘new’ nor exciting, let alone anything to do with ‘space’. Once you’ve seen a metal box you’ve seen a metal box, what more is there to see?

A little shocked by my negativity, I finally decided to notice something I had been staring at but avoiding to see because it seemed so pointless: a black hole opening at the end of a rectangular tube inset horizontally along the top front edges of the boxes, joining them. In finally seeing this comparatively small black hole, it drew my imagination beyond the prejudice that had previously held me back. My thoughts now zoomed along the narrow tunnel’s darkness, aware of the blackness’ constricted space, length, openness and frictionless speed. Then suddenly, I was jettisoned into its opposite: the internal comparatively vast blackness of the first metal box that was closed, contained, motionless and in which I felt stuck.

Shocked, my eyes focused on the box’s metal exterior that now gained a hitherto unthought-of thinness that gave me surprising comfort, in an effort to hoist my thoughts out of the box’s dark insides and back into the light. Safe again, my focus gravitated to the shadowed gap between the first and second boxes that took on a robust thickness compared with the metal thinness sandwiching it on two sides. With this, I finally understood my art history teacher’s exhortations to see our conscious thoughts taking place in this space outside us, rather than in the dark of our physical self (he was, admittedly, German and no doubt brought up on the philosophy that allowed him to draw our attention to this).

Then the slide projector revved into motion as the next slide lunged into view, when I had only begun to see the previous one. How did Donald Judd orchestrate all this space intact with intricate differences that seemingly exploded from nowhere? How was it possible not at first to see what was now so abundantly present, when before all I could see was a row of metal boxes? And how were my thoughts taking place out there, amidst all that, rather than locked away in the privacy of me?

From that day on I have been dedicated to minimalism. While I admit I have, at times, been lazy in my observations and have sometimes been swayed by criticisms before recognising their fallacies, I have never lost sight of how minimalism makes fundamental experience a self-consciousness of our freedom.

The piece by Donald Judd described above, Untitled 1966, was exhibited in the exhibition Primary Structures at the Jewish Museum, New York, in April 1996. In the catalogue for the exhibition, Donald Judd writes:

‘I object to several popular ideas. I don’t think anyone’s work is reductive. The most the term can mean is that new work doesn’t have what the old work had. … New work is just as complex and developed as old work. … Prior work could be called reductive too; … compared to the new work it would even mean less, since then much of its own meaning would be irrelevant’. (ref)

The point here is that every period of art throughout history is ‘reductive’ since it includes less of the period preceding it, to make way for what is new. Use of the term to differentiate one period from another is therefore redundant. Moreover, as one can see by the description of space above, this art involves extraordinary complexity, not reduction. As long as one continues to call it ‘reductive’ one continues to negate its complexity and thereby negate what is truly new.

To move beyond a ‘reductive’ understanding of minimalism, I suggest you start with Donald Judd’s piece included in Less is More. First, free yourself of the limitations with which you might at first perceive it (it’s just a well crafted metal box, open on two ends with coloured perspex inside that sits on the floor and around which I can walk), by finding what you keep staring at but, because of these limitations, keep refusing to see. Then hold on to your hat as you get drawn into an architectonics of space at the very moment of being made, where ‘physics and fantasy are indivisible within an impossible spatial möbius’.(ref)

In the end, you might also find yourself thankful Donald Judd did not dismiss the importance of Lee Bontecou’s art when most did. Thankfully, there is an increasing number of art historians who seek facts over hearsay and who have, as a result, rescued the created space of Donald Judd’s art from the oblivion of misogyny’s tragic graveyard. Foremost, of course, is Richard Shiff, as well as David Raskin, including curators who worked with Donald Judd, Marianne Stockebrand.

As an appropriate ending, then, it is worth having a listen to one of Spoon’s more popular tracks on this 2007 album with Lee Bontecou in her studio on its cover. For uncannily, although the selection of this image was the result of mistaken identity, the track suggests no mistake was made at all but, rather, as the song goes … ‘the call of a lifetime ring’ … (Britt Daniel, The Underdog).

Lyrics here (better listening, too).

NB: Most of what is said here is based on premises established in an extensive manner in: Gail Hastings, The process of specific space: Minimal art generally, Donald Judd’s art particularly, The University of Sydney, 2009.